Services

- Home

- Mental Health Services

- Who We Treat

- How We Treat

- Patients & Visitors

- About

close

“As a veteran myself who was once suicidal, I have lost way too many of my fellow veterans to suicide. The first one was one I deployed with. The second one was someone who I had worked with. The third one sent me on a tailspin; it was my counselor. I had such a hard time processing this.

Here was the person who had essentially saved my life and helped me instill productive coping mechanisms in my everyday life, do the very thing he was trying to prevent me from doing. Even now, five years later, I still have difficulty wrapping my mind around this. The number of veterans that kill themselves each day is too high; one is too many.”

—Ryan Rogers, 44

Veterans like Rogers are often recognized for service, honor, and bravery in the face of warfare. People may view them from a distance as mysterious heroes, but up close they are heroes and regular people. As Rogers so openly shares, veterans have the same relationship issues, self-doubts, dreams, hobbies, and mental struggles as everyone else.

As they return from a deployment to a waiting family and start a job search as their service time runs out, they hear their buddy has taken his or her own life, lost to memories from overseas. That may in turn cause such devastation for the friend, he or she falls into depression themselves as thoughts stray to their shared encounters of vivid experiences as border security.

Daily fear had to be swallowed as they maintained constant alertness, scanning faces and documents, always waiting for an improvised explosive device (IED) to detonate or a child to lead them into a trap. Why would one survive that, only to succumb stateside to a bullet from a self-inflicted gunshot?

Haunting memories, coping with loss, inappropriate sexual conduct by a higher-ranking officer—many different reasons can cause post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans, and even lead to suicide at the rate of 1.5 times that of the average civilian.

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that occurs after a traumatic, disturbing, and shocking experience. The experience can be first-hand such as

It can also occur second-hand such as hearing of the death of a loved one or a first responder assisting a child-pornography investigation.

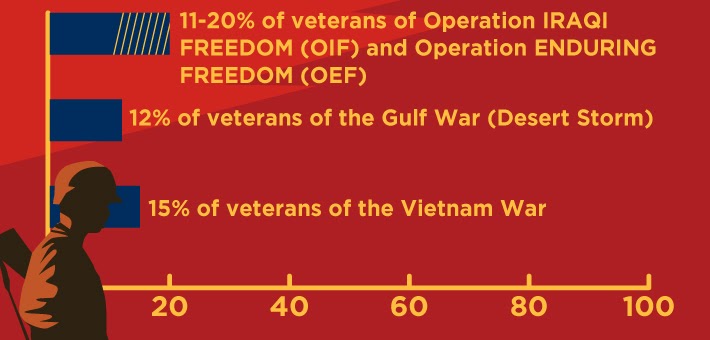

Veterans Administration (VA) services are used by some, but not all, veterans. The VA tracks numbers based on the service era for those who have experienced PTSD:

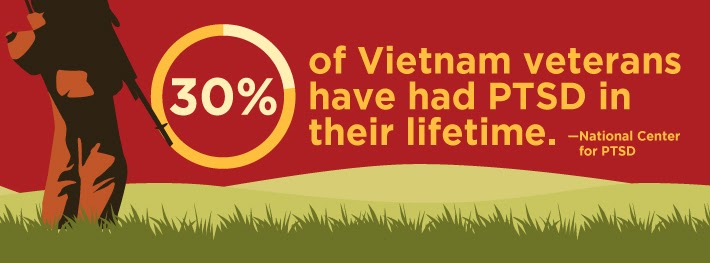

—National Center for PTSD

“For all the traumatic events that people experience, the majority can overcome trauma on their own and heal with no lingering PTSD symptoms,” said clinical psychologist Dr. Justin Baker, a professor at The Ohio State University.

“By and large, people are choosing resiliency—70 to 80% don’t go on to experience PTSD,” Baker said.

For the 30% of people who struggle to overcome the trauma, they experience the four symptoms of PTSD for more than one month and which cause daily functioning problems:

Symptoms generally occur within three months of a traumatic event, but may also show up later in life. Other physical and mental issues, as well as substance use disorders, are not uncommon.

Baker is also the clinical director of the Suicide and Trauma Recovery Initiative for Veterans (STRIVE) housed at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center. The cognitive processing therapy program was founded in 2013 in Utah and relocated to Columbus, Ohio, this past year. The two-week intensive program expects to treat 150 veterans this year.

“Something gets in the way of the recovery process. What got in the way? We sit with the veteran to identify erroneous conditions that led to maladaptive recovery. We help them get a perspective more realistic about the event,” Baker said.

Through cognitive processing therapy, veterans write out impact statements about how their life is different now having experienced this traumatic event. From their impact statement, the therapists begin to tease out erroneously held beliefs, which come to be referred to as stuck points. With the help of the therapist, the veteran begins to challenge these stuck points in a systematic way to create more realistic and accurate understandings of the event or events. Many veterans see a dramatic change after only five or six sessions as their thinking about the event begins to shift, improving their mood and helping them to reengage with the world around them.

“Avoidance is a main symptom of PTSD; large crowds or events are often interpreted as overly dangerous and unsafe. As veterans move through PTSD treatment, they begin to re-engage with their life, go to grocery stores, call people, or go on a date with a significant other.” Baker said.

In the current STRIVE program, all participants are contacted six months and one year after the completion of treatment. For the treatment to be considered successful, we need to know that symptom relief is long term. Baker said data shows a 70% improvement in PTSD symptoms immediately after program completion, with the majority of veterans continuing to report significant improvement six months later. STRIVE hopes to broaden its reach by training mental health professionals around the country with its cognitive therapy program.

Programs like STRIVE and others are developed to reach those unable to recover without some assistance, and before it reaches another level, which could be suicide.

Keeping in mind the relationship between PTSD and suicide, groups like STRIVE aim to improve the mindset of participants by including the development of a crisis response plan, whether the participant has voiced thoughts about suicide or not.

The belief that talking about suicide makes someone more focused on it is inaccurate, Baker said. Having tools to cope with thoughts, and knowing the resources available, is truly beneficial. During the six-month program follow-up, 60% of veterans who started therapy with thoughts of suicide reported a reduction in these thoughts over the next six months.

An editorial in Psychological Medicine, an international medical journal, also disputes concerns that suicide discussion increases suicide ideation or affects the well-being of any groups including adults, children, the general population, and at-risk individuals.

“Our findings suggest acknowledging and talking about suicide may, in fact, reduce, rather than increase suicidal ideation, and may lead to improvements in mental health in treatment-seeking populations,” the editorial concluded.

While Houston and Texas veterans can access STRIVE’s program, there are a plethora of resources available in the local region, due in part to the large military population—active or discharged—in Harris County and the surrounding region.

In 2018 the VA issued a Mayor’s Challenge, followed the next year by the Governor’s Challenge, to encourage local and state levels to enhance services and share successful measures to prevent suicide by service members, veterans, and their families. It also called for a suicide prevention coordinator at local levels.

Brent Arnspiger, LCSW, is the suicide prevention coordinator for the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston. He said the Mayor’s Challenge has resulted in a streamlined effort to connect families and individuals worried about a veteran’s mental health with the right agencies in the region.

Brent Arnspiger, LCSW, is the suicide prevention coordinator for the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston. He said the Mayor’s Challenge has resulted in a streamlined effort to connect families and individuals worried about a veteran’s mental health with the right agencies in the region.

“We have collaborated with organizations throughout the city and the county. Everybody was doing their own thing—the health department, The Harris Center, Easter Seals, Wounded Warrior Project, the city and county.

“When they called the veterans' crisis line and were not eligible for VA services, we could only give them a phone number. Now, we call The Harris Center, for example, and make a referral for the veterans to the appropriate agency. Callers are usually contacted within 24 hours. We don’t have to worry about whether they are getting connected because we make the connection for them.”

Arnspringer said this process is being looked at for expansion throughout the state, with each VA coordinating with local mental health authorities.

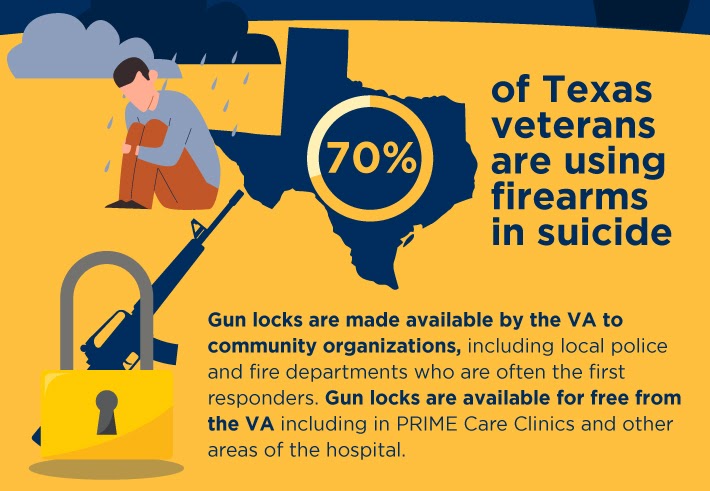

With 70% of Texas veterans using firearms in suicide, he said gun locks are made available by the VA to community organizations, including local police and fire departments who are often the first responders. Gun locks are available for free from the VA including in Prime Care Clinics and other areas of the hospital.

“This is a really important strategy for veterans and families to delay their impulse and keep them safe.”

Another measure is to increase awareness for veterans, families, and primary care physicians of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale to assess feelings and behaviors and determine if further evaluation is needed.

The Harris County Veterans Services Department is becoming a resource hub by working alongside the VA, city of Houston, and with an increasing list of organizations and nonprofits in the county for veterans’ needs that handle their requests, including mental health assistance.

Public Affairs Officer Henry Chan fields these calls, noting “while the Harris County Veterans Services Department was formed in 2019, they already handle up to 30-40 calls a day from benefits claims to veteran emergencies—sometimes including suicide attempts.”

He served four years in the Army as an ordnance officer dealing with munitions and weapons systems before switching gears to public affairs, referring to his time in the Afghan mountains as “the best of times, and it was the worst of times.”

Chan said it can be quite jarring going so quickly to a home environment after combat duty. He pointed out research and awareness have reduced stigma related to veterans receiving mental health treatment.

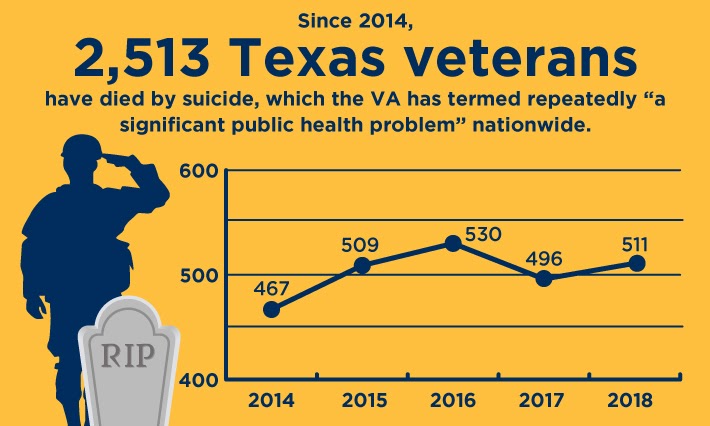

According to the VA analysis of 2018 data released in November 2020, 511 Texas veterans died by suicide, a 2.94% increase from 2017. Thirty were female (5.8%) and the remaining 481 were male. These numbers are compiled by the Department of Defense and the VA and presented in a joint mortality report.

Since 2014, 2,513 Texas veterans have died by suicide, which the VA has termed repeatedly “a significant public health problem” nationwide.

Females have accounted for roughly 5% of Texas military suicides in recent years, except for a 2015 spike to 7.66%. They make up about 9% of the veteran population. They are twice as likely to die by suicide as non-veteran women, with military sexual trauma (MST) being one key component.

For veterans using VA services, they are all screened for MST, and national data shows one in three women and one in 50 men have recorded “yes” in an answer. MST can occur during peacetime, training, or wartime and be inflicted as assault or harassment.

It can also occur from a superior ranking officer or within their own ranks. Having the trauma occur in a war zone, on foreign land, and with fewer females for support, heightens the event creating a multi-trauma event. If untreated, the aftereffects can lead to depression, substance use disorders, and suicide.

Women are less likely to report MST because the majority of those that are in their reporting protocol or who would provide treatment are men. They also fear retribution and find it hard to complete treatment programs because many are single mothers with limited access to childcare.

Abram Williams, 37, of Prairieville, Louisiana, joined the Army in 2000 after earning emancipation in the court system at 17. He ended up seeing combat overseas as part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom(OEF/OIF) and was discharged in 2011 as a staff sergeant.

Abram Williams, 37, of Prairieville, Louisiana, joined the Army in 2000 after earning emancipation in the court system at 17. He ended up seeing combat overseas as part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom(OEF/OIF) and was discharged in 2011 as a staff sergeant.

“I wanted to fight for something and joined. It happened to be one year before 9/11. I saw war at a young age, and it hardened me. My closest battle buddy committed suicide. In my eyes, he was invincible, a superhero, the definition of warrior. When he did it, I didn’t think I stood a chance,” Williams recalls looking back on those days.

He describes a dark time that led to the end of his first marriage, a haunted mindset from his service time, and one fateful night with a gun and too much to drink.

“I was that guy that couldn’t pick up that gun that night because I was too drunk.”

Williams went on to implement his military training to his mental health approach, He took some psychology courses without intending so much to earn a degree but looking for knowledge to broaden his awareness.

He also reached out to the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) “to try to find out what’s wrong with me,” Williams said.

There are nine million veterans enrolled with the VA and 18 million veterans in the United States.

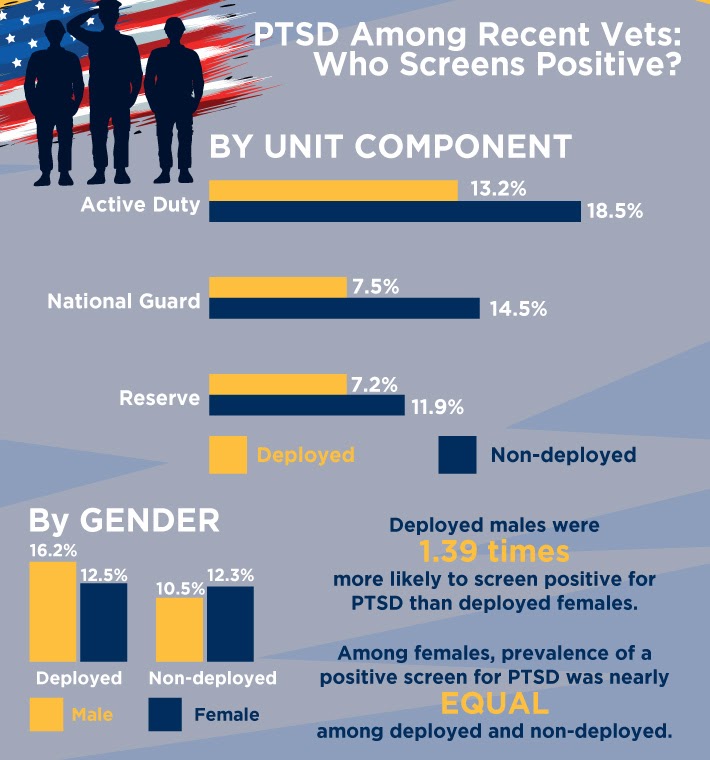

The VA terms PTSD as a “significant public health problem,” for both those deployed (15.7%) and non-deployed (10.9%). The National Study for a New Generation of U.S. Veterans is a health survey sent to 60,000 veterans serving during OEF/OIF. It is also the first study to report positive PTSD results for those who were not deployed and those who do not use VA services.

Veterans may not always choose VA healthcare, and that is important when any veteran statistics are reported, points out Ryan Rogers, director of business management with the PTSD Foundation of America. Founded in 2012 and based in Houston, PTSDFOA has served 1,410 veterans in its peer-to-peer and mentor-based program. Rogers said founder Gene Birdwell was tired of hearing the statistic that 22 veterans lose the battle each day to suicide.

Rogers said the statistics are most likely higher due to being reported by a single source, the VA. Adding loss of life through substance use disorders that develop in the chasm of non-treatment, the organization puts the daily loss of veterans estimate at 25-30, according to its website.

Rogers said the statistics are most likely higher due to being reported by a single source, the VA. Adding loss of life through substance use disorders that develop in the chasm of non-treatment, the organization puts the daily loss of veterans estimate at 25-30, according to its website.

The organization focuses solely on combat veteran trauma through its satellite locations in seven states, ranging from mild to moderate symptoms. Camp Hope, in northwest Houston, is reserved for those with severe PTSD, having reached a level of dysfunction detrimental to themselves and others. Participants spend upwards of four to six months receiving care in a mentor-style program.

Rogers, 44, served in the Army infantry and is working on his dissertation “Suicidality Among Military Members/Veterans and the Root Causes” to obtain his doctorate in human services. He is certified in Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), Safe Talk and Mental Health First Aid and has become a trainer for ASIST and Safe Talk.

He ascribes his passion to help veterans as a passion born from the shock of losing three veterans in a three-week period.

Revisiting Abram Williams in his quest to stop suicidal thoughts and live a happier life, he said he personally struggled with forming a connection with his therapist.

“They have all the criteria and the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatry Association) language. My language didn’t speak to them and theirs didn’t speak to me.”

What finally reached Williams?

“One doctor prescribed me an ink pen and a notebook.”

By writing his thoughts down, Williams was able to express himself more vulnerably, and he found himself less frustrated trying to get his message across. He reads this poem during his public speaking engagements to connect with others.

Here is an excerpt from WAR POEM:

Here is an excerpt from WAR POEM:

War is not as simple as kill or be killed/

It’s a tragic change of lifestyle that leaves you permanently ill/

You’ll dream of the battles/

You’ll wake up in sweats/

You’ll jump at the noises you now associate with death...

...Depression/divorce/drug abuse/

Another drink/another fight/vivid thoughts of suicide/

So I empty the bottle/try to drink it away and finish it with a gun/

I'm too drunk to pick it up/tonight instead of 22 it will be 21...

Williams also attended the PTSD Foundation of America’s Camp Hope in 2015, where Rogers works. Williams is married and has four children. He is pursuing his dream to start a ranch where he can help other veterans regain their confidence and fight through hard work and challenging outdoor adventures.

Resources for veterans and families experiencing PTSD or a suicidal crisis can get trauma-related assistance at SUN Behavioral Houston, an accredited facility located in the Texas Medical Center:

For more information about SUN Behavioral Houston’s full continuum of services, call 713-796-2273.

To learn more about a program in this article